The Invisible Illness

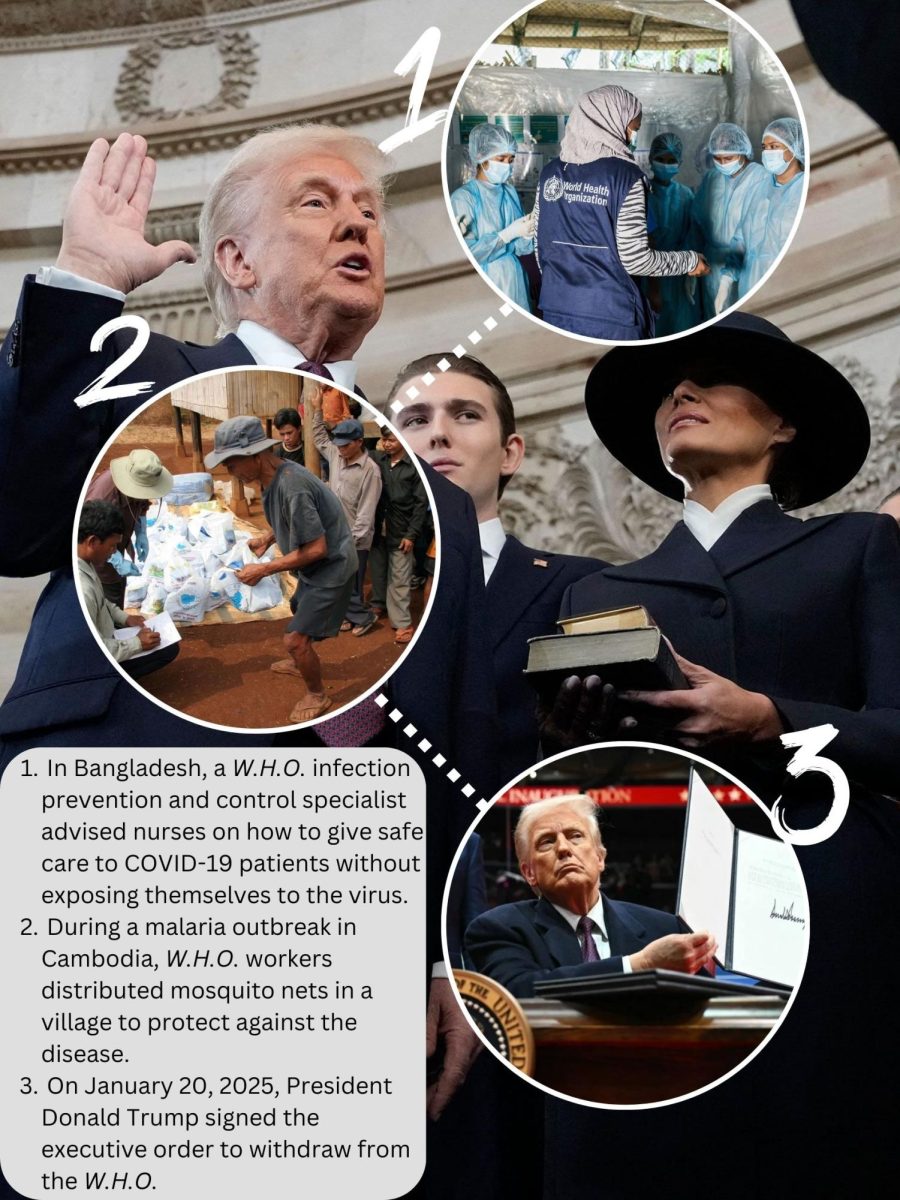

(Above) The invisible illness manifests itself when it gets to the point of a patient crashing down, not being able to function in his or her normal state. A case representative of this idea was when I was admitted into the hosptial. For months since the start of school, I had been working over the present symptoms in my life. However, sometimes it gets to a point where medical intervention is needed. I was constantly hooked up to a new IV bag, my vitals were taken every four hours, and multiple specialists visited me to try to narrow down what was wrong, or if it were just a flare up of symptoms. Photo courtesy of Mrs. Jennifer Reif. Graphic courtesy of elleandtheautognome.wordpress.com.

September 12, 2022

During high school students may feel invisible from time to time, but imagine being a student with a different type of invisibility. Invisible illnesses affect more people than one might think, since anyone can pass under the radar of, “Not looking sick.” In high school there are set expectations for every student, including taking rigorous courses, playing a sport, volunteering, getting into a top college, having a social life, and overall being the perfect well-rounded student. While all of this combined is already difficult for an average teenager, adding on chronic conditions magnifies the lack of ability to maintain a level of normalcy.

As someone who struggles with multiple chronic illnesses, I have been to countless doctors appointments with very few doctors actually believing what I say. Now some of this medical gaslighting may have to do with my demographic, being a teenage girl. Commonly, doctors may refer to my symptoms as being part of anxiety, or the fact that I’m not old enough to have health problems. However, it also has to do with the bigger picture of me looking just like everyone else. I don’t have medical devices to indicate I’m sick, I don’t miss extended periods of school, and I don’t talk about my symptoms or struggles very often.

One of the hardest parts about dealing with an invisible illness is that so many people don’t understand it because they can’t physically see it. If I were to be in a wheelchair, or have a PICC line, or wear a brace, or have a service dog, the first thought in peoples’ minds would be, “What’s wrong with her?” Instead, for anyone without one of these medical devices or mobility aids that help improve people’s quality of life, I appear to be fine.

The main chronic illnesses I deal with are Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS) and Hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (HEDS). To name a few general symptoms, I endure extreme fatigue, dizziness, blurred vision, fast heart rate, and brain fog on the POTS end. On the HEDS end, I often experience joint dislocations and pain. These illnesses can come about at any time in an individual’s life, whereas I developed mine at a prime time in high school: tenth grade. Teenage years are supposed to be spent at football games, going to the beach, and hanging out with friends; they’re supposed to be the time with no worries in the world. Yet mine have been spent in doctor’s offices, getting every possible test done, only to still be misdiagnosed while not knowing what is going on. This is common with invisible illnesses. This lack of knowledge often occurs for the obvious fact that sicknesses can’t be seen, and also that so many symptoms overlap with other chronic conditions, which makes what is happening unclear.

As lucky as I am to be able to still go to school or be social, it doesn’t make me any less sick. Sometimes I do have to miss school, because I feel so fatigued, to the point where I can’t get out of bed. Nonetheless, the next day I’m back at school and dance: the two things that fill up my day. Because of this “inconsistency” with what I am able to do on a day to day basis, I am constantly hammered with, “If you’re still able to participate in those things, then you must not be sick”, or, “How are you able to do one thing one day but not the next?” The best way I can describe this phenomenon is that I feel like I’m constantly in a fight or flight mode. During the school week I’m fighting, going to school everyday to see my friends and pass my classes. Once Friday afternoon hits, I’m back in flight mode: I need as much rest as I can possibly get, and it feels as though every symptom hits me against a brick wall. Every week the cycle starts over again.

An invisible illness can bring countless insecurities and self-doubt. With society not understanding what you are going through, it can almost make it seem as though I am making up these symptoms, after so many misleading opinions have been set my way. It can almost make those with illnesses think, “Are these symptoms real, or are they just in my head?” On the other hand, it can spark a new level of confidence and determination, through advocating for oneself. This advocation consists of doing research, finding doctors, and explaining to those around you what these illnesses are.

There will be a never-ending stigma around invisible illnesses, and the question such as, “Are they even real if you look perfectly fine?” will always be up in the air. Even so, it is up to the invisible illness community to portray that looks do not determine someone’s well-being.

As much as struggling with chronic, or lifelong, illnesses can suck as a teenager, the feeling of isolation brought along with them can be worse than the actual symptoms themselves. This isolation is introduced through individuals not believing you and feeling like no one else understands anything that you are going through. However, contradictory to this common mindset, there is another world full of people battling these conditions that feel just as invisible. Alongside the community, close friends and family also make a great support system.

Invisible illnesses as a whole disrupt what a teenager envisions as a normal life. They put another stress into a time that should be solely focused on school and hobbies. Albeit, symptoms do not define anyone; all they do is put a detour into the road ahead. As I’m sitting here writing this piece, a million things are going on with my body. I feel lightheaded, the room is slightly spinning, and I’m exhausted, but I bet that the world can only see a teenage girl writing an article. Unseen, unheard, unnoticed: invisible.