There is almost nothing more divisive in the fashion industry than the use of fur. Fur shoes, fur coats, and fur hats can be bought at virtually every high-end fashion retailer; yet their sales accompany decades of protesting and animal rights activism. Exactly when the first people began to use fur as a way to shield themselves from the cold is uncertain. Nearly 40,000 years ago, Neanderthals harvested fur from bison and wooly mammoths in Eurasia, but the first documented time fur was used as a status symbol dates back to Egypt 2,000 years ago, as pharaohs brought leopard hide into their tombs, according to osu.edu. In the early 17th century, with the merging of the Eastern and Western hemispheres, the fur trade from French Canada to Europe flourished. From what would later be credited for building a respectful relationship between Native Americans and French colonizers, Natives taught the French how to trap mainly beavers. This new continent for raw materials, along with the frigid temperatures of the Little Ice Age, sparked a newfound necessity for fur. Thus, the use of fur fortified itself in the fashion world.

But now, with the commercialization of garments and the displaying of fur as a status symbol for the elite, fur has turned from a necessity to an aristocratic aspiration. For example, in the 1951 edition of Vogue magazine, Lisa Fonssagrives, who is regarded as the world’s first supermodel, is featured in an ankle-length mink coat, and Elizabeth Taylor in the movie BUtterfield-8 steals a black fur coat leading to a chain reaction of unfortunate events. This popularization of fur in the media, along with an increasing amount of consumerism, led the everyday American to dream about sporting the latest fur.

However, it was not until the mid-60s that whispers about the ethical consequences of fur came to light. In 1968, the Audubon Society protested in front of Saks Fifth Avenue, responding to the sale of endangered cats’ hides. While these activists did not concern themselves with traditional fur such as mink and beaver, faux fur companies who sought to provide a cheaper alternative rather than a moral solution found an opening. “Timme-Tation” fake furs launched an ad campaign to echo the words of animal rights activists via celebrities such as Doris Day and Mary Tyler Moore in 1971. In it, Day comments, “A woman gains status when she refuses to see anything killed to be put on her back. Then she is truly beautiful….” Because of this campaign, even though it was fueled by corporate greed, the faux fur industry began to break the stigma that their product only targeted lower-income groups and expanded fur into a moral issue.

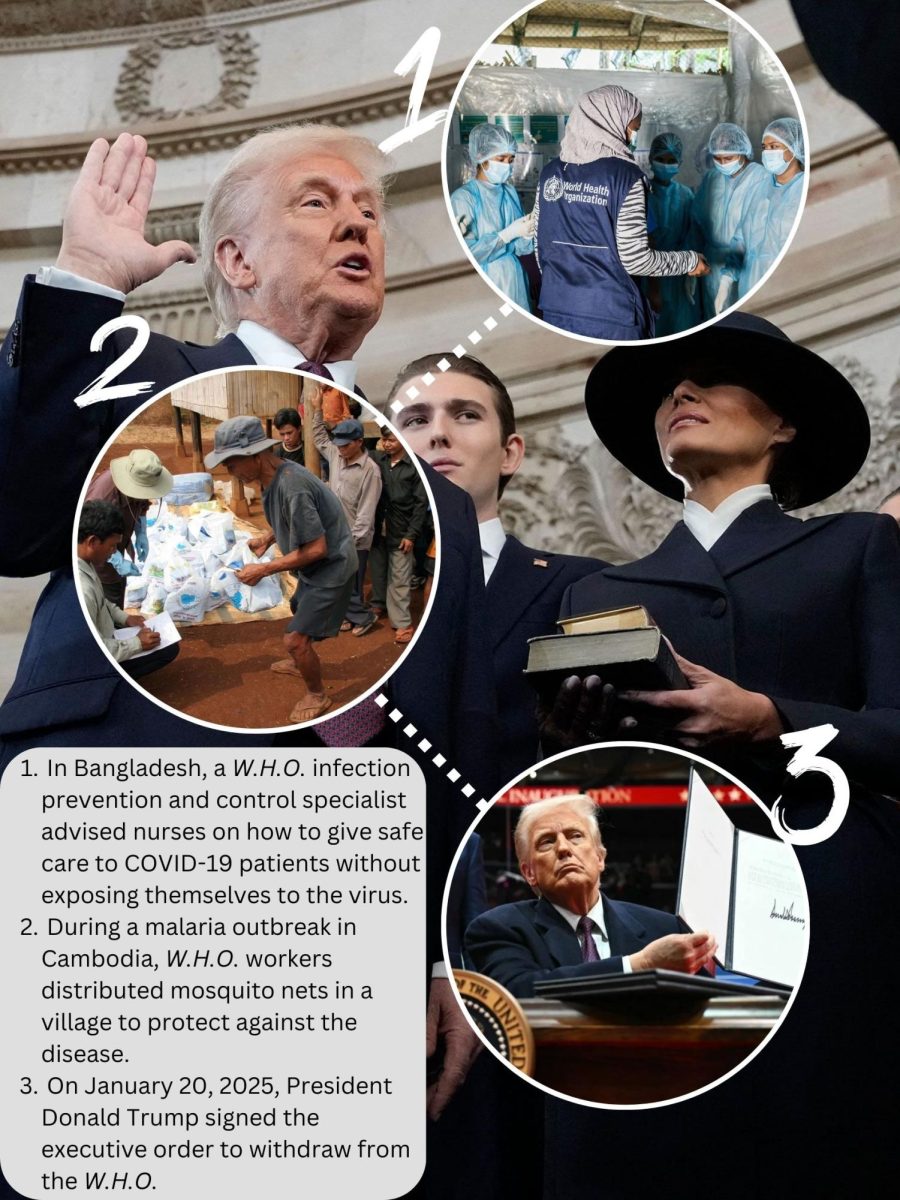

Eighty percent of the fur used in clothing comes from fur farms. Similar to puppy mills, fur farms house thousands of animals, often mink, fox, and raccoon dogs with minimal provisions in small cages out in frigid temperatures. When these animals reach one year of age and their coats are at their prime, they are killed by gassing or electrocution. In 2015, the Humane Society International investigated a fur farm in China, the largest producer of fur, and reported that the foxes and raccoon dogs were beaten to death. As terrifying as this all sounds, it is all to say that the separation we place between the fur on the hoods of our coats and the living, breathing animal it comes from isn’t so separate at all.

As for the other 20% of fur, it comes from trapping. Most fur trapping is concentrated in North America and Russia because over 100 countries, including the ones in the European Union and China, have banned its use (mostly due to the fact that it poses a risk for privately owned animals such as dogs and livestock). While fur farming exists on a much larger scale, trapping is regarded as being ethically worse. Wire traps pin the animal (coyotes, lynxes, bobcats, and foxes) by either their foot or neck and leave it to starve to death or die trying to get out. Traps found in the water drown the animal instead. Not only does this sound barbaric, it poses a risk to endangered animals, such as mountain lions, getting caught in steel-jaw traps.

In response to animal rights protesters and the growing faux fur industry, haute couture houses have been changing along with it. Ralph Lauren was one of the first, switching to fur-like fabrics such as shearling in 2006. They were soon followed by Prada, Gucci, Armani, and Vivienne Westwood a decade later. This new wave of both ethically and socially conscious retailers heralds a new age of fashion: an age of looking beyond the finished product and beginning to critique it in terms of sustainability and moral principles. Fur is outdated and inhumane, and it is about time that it becomes prohibited.